Why do we often struggle with some of the seemingly simplest things, like slathering screen-printing ink onto a decorated-apparel garment. Slathering so that it looks clean, bright, opaque and altogether attractive.

Let’s delve into troubleshooting for screen printing. Troubleshooting often involves breaking down the processes involved in screen printing into each component and looking at how each step can impact the next or the overall outcome. My goal here is to outline which processes are key to ensure a positive outcome.

One of the first things I will address is the category of screens; specifically, film and emulsion. Tension? We’ll get to that, but what’s the point of having a tight mesh if the image on the mesh is not right.

Finding the Right Transparency Film for Screen Printing

Let’s look at film. Opacity is the name of the game when it comes to obtaining a clear, clean and detailed image. The question you should ask yourself is whether the image on your film is opaque enough? To be clear, we are talking about the black image on the clear film.

Notice the differences between the three mediums being used here and how the ink is darkest on the Ortho (left), Inkjet (middle), followed by Vellum (right). Photo courtesy

of International Coatings

To be honest, unless you are using true film (the kind they used back in the day for actual photography; the stuff that required liquid bath of chemicals to develop), all the digital inkjet type films are not as good as the old school (Kodak, Agfa, etc.) type Lithographic film. These films were opaque! No light would penetrate. It contained actual silver particles that could be recycled.

With all the digital film outputs now, I have not seen one that compares to the quality of yesterday’s true films. Because of that, we must adjust our screen prep to the common denominator, the lowest factor: How “un-opaque” is the film I am trying to use to burn my screens? Yes, I said “un-opaque.” The degree of how un-opaque, or transparent, your film is.

If the film were 100-percent opaque, then this wouldn’t be an issue. It’s how un-opaque it is that creates the issue. You must expose the screen with something less than ideal film opacity because of how un-opaque the film positive is. The film’s opacity is one of the most important factors in creating the best image.

Try adjusting your print settings or asking the film manufacturer to help you adjust your printer settings so that it prints out the darkest print possible. In the past, I’ve been able to use the “absorbent” paper setting (bond paper, for example) on the printer, so that the printer spits out more ink. The film has a coating that absorbs the ink; therefore, more ink translates to a darker print.

Executing Screen-Printing Emulsion

One of the first things on my agenda when visiting a shop is to review the freshly developed screens (screens that are ready to go on a press). Can I see the edge of where the film was? This could be a sign of under-exposure. Is the screen tight enough? It doesn’t have to be in the highest level of tension, but it should be in the ballpark. Can I feel where the image begins or ends due to the thickness of the emulsion? If I don’t, then we don’t have enough emulsion.

I don’t care if it is a 110 mesh or a 330 mesh, you should always feel where the image is if you close your eyes and touch the screen. When reviewing the emulsion, you should not see pinholes. If there are a bunch or the screen maker blocked them out after developing, then you may have a dirty shop/glass or film or you may simply not be degreasing your screens properly.

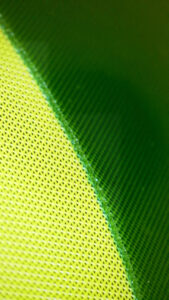

In this zoomed-in view, you can see the detailed emulsion coverage on the screen being used. Image courtesy of International Coatings

Let’s do a test: Now that you’ve reclaimed your screen (or starting off fresh with a new screen that has been degreased), open a fresh container of emulsion. Coat the screen according to the emulsion manufacturer’s recommendation. I typically do two coats on each side with the ink side last. Let the screen dry with the ink side up.

After the emulsion is dry, take some electrical tape, something that is positively not going to let light pass through. Place it in the area you would normally place your film on the screen and expose it. If your screen comes out well, then the film quite possibly could be the issue. If your screen does not come out well, let’s troubleshoot what the issue could be.

For that, do the same test but this time, take the tape and place it on the image area. Leave it on the drying rack for a day or two, with the tape and shirt side up. Then simply wash the screen out. If the area you placed the tape on washes out before the outside area does, then you have light contamination in your dark room.

Store your dry coated screen in a light safe place. One of the top, if not THE top issue, is storage of your coated screens or even your emulsion before it is applied. Emulsion is light-sensitive. But I think many printers underestimate how important it is to store both the liquid emulsion and the coated unexposed screen in the darkest environment possible.

Sometimes when I’m working in an area with a lot of light (maybe there is a window nearby) or I must walk from the exposure area to the wash-out area, I will put the screen in a black plastic bag or even a cardboard box, anything to protect the screen from the light poison before washing it out. You can even turn off the wash-out booth light and only turn it back on after you are sure you have washed out the screen.

Several months ago, I was asked by a busy shop to help them troubleshoot their processes. The main thing they were concerned about was printing the best white on a shirt. When I walked into the shop, diagnosing the problem was not difficult. Their screen room had open doors to the rest of the office, so the room itself was not even dark. In addition, the exposure table was also located in the room emitting light every time they used it. This is the worst-case scenario.

To top it off, the washout booth was located immediately around the corner of the screen drying area, preventing the screens from thoroughly drying in a timely manner. It only “worked” because they would coat the screens as they needed them.

There was no other way, as any screen left in that room for any duration of time, even overnight, would not work. If they had done the tests I mentioned above, they would have quickly found out that their coated screens were all light contaminated.

If there is white light flooding the room every time you open the door to retrieve a screen, then that should be fixed. If you need to turn on the white light to coat the screen so you can see, then that should be fixed. I’ve used yellow, fluorescent lamp sleeves and that helps but the yellow is still too strong. The red sleeves are better. Treat your screens as if they were in a hospital operating room, clean and uncontaminated from humidity, dust and light.

Film and emulsion quality are key to having a great image.

Screen-Printing Squeegees & Blades

One of the attractive things that drew me into screen printing back when I was 14 was the hands-on artistry aspect of screen printing. Our hands and skill set have a lot of influence on the end result. Let’s examine the squeegee, an indispensable tool that can determine the outcome of a print for better or worse.

Have an array of squeegees of various durometers. Photo by photo_gonzo – stock.adobe.com

Take the squeegee durometer, pressure and angle or how quickly the squeegee is pulled across the screen. All these factors can determine how much ink is deposited onto the screen. Other simple habits, such as flooding a screen can also make a huge difference: Do you simply flood the screen (move the ink from one area to the other), or do you force the ink into the mesh while you are flooding? When flooding, the angle of the blade, pressure and speed can certainly influence the print stroke. When details matter, such as on designs with small details or fine lines, or on a four-color process design, forcing the ink into the mesh with a flood stroke is crucial.

Just beware too much flood pressure can add too much ink, while not flooding the mesh at all can result in too little ink deposit. Find a good balance depending on the print.

What about the actual squeegee? Is it fresh? Over time, frequent use and cleaning can make blades hard and brittle. Some cleaning solvents can affect the aging of the blade more than others.

Purchase fresh squeegees with no nicks or scratches, ones that have the correct hardness/softness durometer. Don’t get the same durometer on all your squeegees. Maybe grab 65- or 75-durometer medium blades. Then you’ll have one that is softer and one that is harder. Don’t worry, this is one of the cheapest upgrades you can do in a shop; yet it’s one of the most overlooked ways to improve the overall quality of your prints.

Ideally, a selection of different durometer squeegees should be available for each of the print stations you have.

Variances in Screen-Printing Mesh

Not all mesh is made the same. If you do thorough research, you’ll find that “you usually get what you pay for.” Get some screens from a reputable source that uses rebuttable mesh. Check that the mesh is a low elongation type. Keep in mind, some mesh comes from another industry—like the filtration industry—and is not specifically made to be stretched to such a high level. Rip resistance is the main factor they avoid.

Capillary film was used for the HD Clear 141 mixed with Metallic Silver 96 ink. Photo courtesy of International Coatings

Meshes that are specifically made for screen printing are designed to be stretched and printed through. This means the mesh is more stable under tension, and when stretched properly, has a greater mesh opening or percentage of open area. A larger open area will allow ink to flow through more easily and under less pressure, thus giving you a better image.

Be aware that different manufacturers may use different thread thicknesses for their mesh. Some use thicker threads, maybe to avoid frequent ripping. Others use thinner threads that may rip easier but are worth every penny. Think of a mesh made of rubber bands. Now imagine the rubber bands getting thinner when they are stretched out. When the mesh is stretched properly the threads become thinner, it opens the area of the mesh that the ink passes through, making it easier to print using less pressure.

Let’s briefly discuss mesh tension. Earlier, I mentioned mesh tension as one of the key ingredients to a quality imprint. Have you ever used a cheese cutter that uses a thin tight wire? Well, imagine trying to slice the cheese with a thick, loose wire. Not easy. Now, imagine slicing cheese for a living, and you want to make more money. The only way you could make more cash is by slicing faster. Screen printing through a tight mesh simply makes it easier and faster.

Remember the big shop I mentioned? They really do not like to double stroke any of the colors. Why? Because doing so can cut the rate of the prints per hour by 30 percent or more. Less prints per hour means less income. They will adjust everything (squeegee, mesh type, emulsion, etc.) to perform at peak level to achieve the maximum rate.

I have often been contacted and asked for help to assess a problem at a shop. The first thing I like to do is to check the quality of the current screens they are producing. Is the mesh tight? Is there enough EOM or thickness of the emulsion? Are there too many pinholes? Can I see the edges of where the film was? Like in medicine, there are symptoms or signs of an unhealthy screen.

Correctly Curing Screen-Printing Ink

I often get complaints regarding ink not curing. Plastisol-based inks (which can also include water-based inks) need heat for the ink compounds to fuse and “cure.” Regularly test your prints during a production run to assure that the ink is truly cured.

The white underbase for the Thai Warrior design. Photo courtesy of International Coatings

To do so, stretch the “cured” print to see if it cracks too easily. Sometimes there is simply not enough ink. Otherwise, check the dryer settings. Is the temperature high enough or is the belt speed too fast? Check whether the temperature is set at the correct setting for the type of ink you are using, either standard cure or low cure.

I often find that the temperature is set high enough, but the dryer belt speed is simply too fast. Plastisol inks need to be cured at the suggested temperature for at least one minute. Water-based inks typically need even more time than. that. I assure you that the ink manufacturers thoroughly test every batch of ink before they package each lot of products.

Often the dryer is being pushed to consume more shirts to increase productivity. I’m referring to “pushed,” because you may have three machines feeding one dryer and in order not to slow down the money machines, the speed of the dryer belt is increased to accommodate the number of garments being printed. This is understandable but let me warn you: time in the dryer is your friend and heat is a necessary evil. You need the minimum temperature to cure but no more. If you push the dryer by placing more garments at a faster speed, the ink may not correctly cure.

Let me give another scenario: black ink on a plain white garment cured great, but today the layers of ink on the red garment seem to crack. Same dryer settings for both, what could be wrong?

Were any additives included in the ink, for example, reducers, pure pigments or a catalyst, that could be affecting curability? Or you may have a standard cotton white T-shirt with a simple black print that doesn’t require a long dwell time in the dryer. Are you combining it with other types of prints in the same dryer? A red polyester blend garment, perhaps, that is more sensitive to heat? One with a thicker ink deposit, so you need a longer dwell to cure the stack of thick inks (Blocker/white/color)?

It can be very difficult curing different types of print and/or substrates at the same time or belt speed. If you increase the dwell time to accommodate the poly blend garment, the white shirt could get scorched. Inversely, if you lower the cure temperature to prevent the red fabric from bleeding, the ink on the white shirt may not cure completely. There simply isn’t a “set it and forget it” setting.

This in-house design depicts the vibrant results you can achieve with the right tools. Photo courtesy of International Coatings

Remember, time is your friend, and heat will become your enemy if not properly managed.

If the belt speed seems to be correct, use a donut probe to see if there are any cold spots in the dryer. The probe can show if the dryer’s internal temperature correctly matches where its temperature is set.

Many large shops producing tens of thousands of prints per day have a designated person who roams from dyer to dryer throughout the shift. Their job is to document the dyers’ temperatures and create individual profiles of each. Then they adjust the individual dryer settings when necessary to avoid any potential disasters.

Every dryer has a personality, and over time you can anticipate any variables that may come up. For example, if it’s raining or windy outside, or if a garment is being printed that has a high poly content, or a print with a thicker ink film deposit, all these factors and countless more, can affect the cure.

In the end, washing your garment a few times will give you peace of mind or can keep you up at night. Cured ink will stay on the garment during the wash, whereas uncured ink will come off. The good thing about plastisol is you can always re-run it through the dryer to correct an under-cure situation. Other types of inks may not give that option, so as they always say, doing it right the first time is always the best option.

Kieth Stevens is the Western regional sales manager for International Coatings. He has been screen printing for more than 42 years and teaching screen printing for more than 12 years. He is a regular contributor to International Coatings’ blogs; and won SGIA’s 2014 Golden Image Award. He can be reached at [email protected]. For more information, visit iccink.com. You can also follow the company’s blog at internationalcoatingsblog.com.